- News

- City News

- bengaluru News

- Karnataka’s consumer courts achieve 95% case disposal, but filing of complaints still very low

Trending

Karnataka’s consumer courts achieve 95% case disposal, but filing of complaints still very low

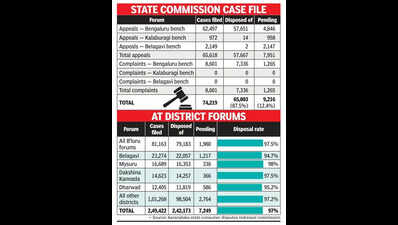

Bengaluru: Consumer courts in Karnataka have recorded a high case disposal rate of 95%, with more than 3 lakh cases resolved out of approximately 3.2 lakh filed across state and district commissions as of Feb 2025.

While this points to the efficiency of forums in disposing of cases, the data indicates that despite the Consumer Protection (CP) Act being in force for over three decades, formal complaints through official channels remain relatively uncommon compared to the volume of consumer transactions occurring daily across the state.

You Can Also Check: Bengaluru AQI | Weather in Bengaluru | Bank Holidays in Bengaluru | Public Holidays in Bengaluru

The fact that only 3.2 lakh cases have been filed since the inception of consumer forums in 1989 is reflective of limited public awareness about consumer rights and redressal mechanisms, possible procedural complexities that may discourage filing, and the time and resources required to pursue cases.

That said, despite all efforts, there are cases where people haven't received the money even after all the trouble, as companies don't pay up despite court orders. Sources said this has happened with 10% of cases.

Consumers can also seek criminal action under Section 72 of the CP Act for non-compliance. "We rarely see those cases but when it does happen, we send notices to police asking for execution," the official explained.

Disposal rate analysis

The district commissions demonstrate remarkable efficiency with a 97% disposal rate, having resolved more than 2.4 lakh cases out of 2.5 lakh filed. In comparison, the state commission shows a slightly lower but still significant 87.6% disposal rate, with 65,003 of 74,219 cases disposed of.

The disparity between disposal rates at different levels may reflect the greater complexity of cases reaching the state commission, which often handles appeals and more intricate consumer disputes.

Among the district commissions, Bengaluru Urban leads with 32,151 cases filed, followed by Belgavi (23,274), Mysuru (16,689), and Dakshina Kannada (14,623). The Bengaluru Urban jurisdiction, including its four additional benches, accounts for approximately 80,262 cases, representing nearly one-third of all district-level filings.

Rural and smaller districts show significantly lower filing numbers. Yadgir (390), Ramanagara (152), and Chikkaballapur (148) report the fewest cases, highlighting a potential urban-rural divide in consumer forum utilisation.

Bench performance at state level

The state commission's Bengaluru bench handles the overwhelming majority of appeals (62,497), while the Kalaburagi and Belagavi benches show minimal disposal rates despite having 972 and 2,149 cases filed, respectively. The Kalaburagi bench has disposed of just 14 cases, while the Belgavi bench has resolved only two cases, raising questions about operational efficiency or resource allocation.

Notably, complaints at the state commission level are filed exclusively at the Bengaluru bench, with none registered at Kalaburagi and Belagavi benches.

Efficiency variations

District commissions in Chamarajanagar (99.5%), Hassan (99%), Kodagu (99%), and Shivamogga (99%) demonstrate the highest disposal rates. Conversely, Belagavi (94.8%), Dharwad (95.3%), and Chitradurga (93.2%) show comparatively lower efficiency.

Among newly established districts, Chikkaballapur has the lowest disposal rate at 77%, followed by Yadgir (78.5%) and Ramanagara (84.2%).

Overall, the data presents a paradox: While consumer courts demonstrate high case resolution efficiency, they appear underutilised by the population. The stark disparity in filings between urban and rural districts indicates possible geographical and socio-economic barriers to access.

End of Article

Follow Us On Social Media